Relocation to Restoration Part 1: A Dangerous Mix: Hurricanes and Hazardous Chemicals

This blog is reposted from Cherokee Concerned Citizens

The Cherokee Forest neighborhood is located in a high risk flood zone (Zone AE) as shown in the FEMA map below. While this is true of most homes in Pascagoula, the term "high-risk" takes on far deeper meaning for Cherokee Forest residents. Their neighborhood is situated at the edge of Pascagoula’s industrial corridor –in the shadow of heavy industry, shipbuilding and petrochemical plants. As hurricanes become more intense and flooding more frequent, residents of Cherokee Forest are forced to contend not only with water damage but also with potential chemical exposure, toxic releases, and long-term health consequences.

NFHL Interactive Map Tool: The blue pin represents the center of Cherokee Forest subdivision. To the right is an aerial view of Bayou Casotte Industrial Park. Note: Not all facilities are pictured. LNG terminal to the South and Enterprise gas processing and the second phospho gypsum stack (MS Phosphates Superfund) are located on the north end of Bayou Casotte Industrial Parkway.

Mike and Jackie Devine, long-time residents of the neighborhood, recall the danger vividly. They rode out Hurricane George in 1998 with their two children, huddled in a bathroom as rising floodwaters and violent winds battered their home.

“There was an extremely strong chemical odor that burned our eyes and throat,” Mike recalled. “The odor was so strong that it was hard to breathe. I told them to take a towel, wet it, and put it over their nose and mouth to help ease some of the burning.”

They knew better by the time Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. The family evacuated—but when they returned, they found their yard littered with barrels of chemical products and over $100,000 worth of damage to their home. They were not alone. Every home suffered at least some damage. For some, all that remained was their home’s foundation.

“If we are going to have a severe hurricane, to protect my family, we leave. I have no control over nature or the chemicals at these [petrochemical] plants in our area.”

Chevron reported “minimal” damage from Katrina—citing a 20-foot dike built after Hurricane Georges. Chevron reported damage to cooling towers, marine terminals, and tank infrastructure and released an unknown quantity of chlorine gas flaring as a result of a damaged tank. The BP gas processing plant reported no releases during Katrina, but two weeks after the storm, the company reported a release of 1,460 pounds of nitrogen oxide due to flaring necessitated by pipeline damage. Mississippi Phosphates flooded with more than 15 feet of water and released anhydrous ammonia gas.

Oil tanks at the Chevron refinery in Pascagoula are surrounded by flood waters from the surge of Hurricane Katrina. Joe Ellis, The Clarion Ledger.

After Katrina, the EPA conducted limited sediment and surface water sampling at several industrial sites and found concerning levels of heavy metals, dioxins, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The EPA concluded, however, that the results fell within acceptable health risk ranges, largely in part due to the likelihood of minimal prolonged human contact at the site. Yet no samples were taken from Cherokee Forest itself, despite its proximity and the clear evidence of offsite contamination.

The Risk to Health & The Burden of Proof

Numerous residents have reported chronic respiratory issues, fatigue, headaches, digestive issues, and sinus problems. In the last six years alone, there have been 30 deaths from cancer, heart, and lung disease—unrelated to COVID. The impacts are cumulative, complex, and all too real.

According to ProPublica investigative research, the Cherokee Forest neighborhood is considered a cancer hot spot with some households at risk of cancer 3.4 times more than what EPA says is acceptable.

The residents of Cherokee Forest are living with many unknowns. Pinpointing the culprit is challenging especially when there are multiple facilities nearby releasing many of the same carcinogenic toxins into the air, water, and land and when all of the environmental testing stops at the property lines of industry.

But when so many residents experience similar symptoms and the number of deaths in such a small area defy explanation, people start asking questions. And when the regulatory agencies fail to provide answers, the community is left to find their own answers – often uncovering just one small piece of a bigger puzzle and often with more questions than answers.

One Cherokee Forest Residents Story

Linda Ferril’s husband had never been allergic to bees. But after being stung while cutting grass on Martin St (about .7 miles away from Cherokee Forest), he was hospitalized nine times with symptoms that baffled cardiologists and pulmonologists alike: chest pain, fluid in the lungs, and dangerously high blood pressure. Eventually, a Jackson cardiologist tested him for histamine levels and diagnosed him with mast cell activation syndrome—a condition in which the immune system overreacts and floods the body with chemical mediators.

The trigger? No one knows for sure. But the doctor couldn’t rule out exposure to environmental toxins.

There is research suggesting a link between low-level, long-term exposure to heavy metals and immune system dysregulation, including mast cell disorders. It’s possible that the bee stings were just a spark that lit a toxic fuse. It’s hard to know. But stories like the Ferrils’ are common in Cherokee Forest.

““I hope my story helps others—especially others in the neighborhood with similar symptoms and whose doctors can’t explain what is happening to them.”

Since 2015, the CCC have conducted their own investigations – taking air, water, and soil samples, monitoring fugitive emissions, conducting health surveys, and taking bio samples. Some have proven inconclusive while others are clear indications that the residents' concerns of health impacts need to be taken seriously.

The most recent study completed in partnership with researchers from the University of Colorado and University of New Hampshire found elevated levels of nickel in the toenails among a small subset of children living in the neighborhood. While the study could not pinpoint where the nickel came from, it did note that Rolls Royce was listed in the TRI as one of the top emitters of nickel in the state.

Upon further investigation (after the study was completed), the CCC learned of other potential sources of nickel include Chevron Refinery and what is now Bollinger shipbuilding. The refinery by far releases more of this dangerous chemical in the form of nickel compounds. The known health effects include body weight, cancer, hematological, immunological, and respiratory conditions.

Relocation to Restoration: A Win-Win Strategy

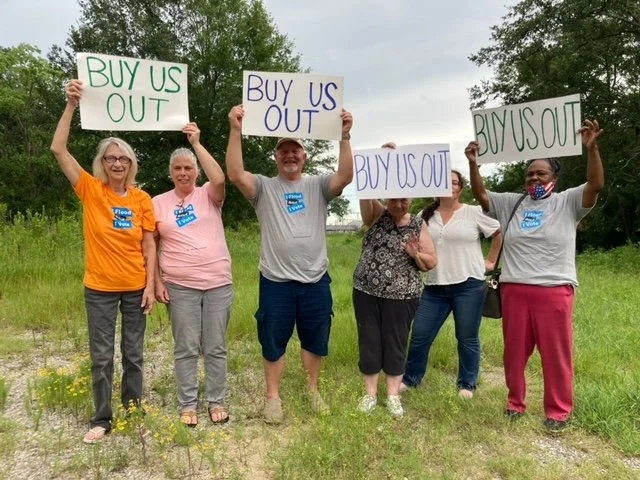

After more than a decade searching for answers, the Cherokee Concerned Citizens (CCC) have concluded their best chance to protect the health of their families is to move out of harm’s way for good and before the next big storm comes.

“We have a house we can’t live in; we have a house we can’t rent, and a house we can’t sell”

Cherokee Forest residents, photo courtesy of Anthropocene Alliance (A2)

In 2024, the CCC, in partnership with Buy-in Community Planning, officially launched the Relocation to Restoration (R2R) project to develop a plan to relocate Cherokee Forest residents out of harm's way. The goal of the R2R project is to convert bought out parcels into a blue/green buffer along the Industrial zone.

To support this planning process, the CCC and Buy-in hired a design-architecture firm and established a Technical Advisory Panel (TAP) with a diverse team of professionals with expertise in environmental and industrial science, ecological and habitat restoration, and climate resiliency. Check out Part 2 & Part 3 of this series to learn more about the site conditions the TAP observed during their visit in February 2025.